I was introduced to jazz through my parents, both of whom had impeccable taste. Like rap and blues, jazz is pure hypnosis when it is done right. The catch is that it very seldom is.

Last time the world ended back in 2012, I spent a summer working through Levine’s textbook on Jazz Theory. This was my first serious engagement with the genre. Most of the songs it referenced, even those I’d heard, I had never truly listened to before. All of this is of course pathetic. Any real jazz head would see such paltry education sitting somewhere between a good start & a bad joke. I could spend another decade working through Levine’s book to truly understand it, and there would be a thousand new worlds to learn after that. Jazz is a foreign country and I’m worst kind of American: a tourist.

About five years later, I spent several seasons reading Irving Berliner’s encyclopedia of autism anthropology, Thinking in Jazz. I savored it because I realized, like Schmidt & Eno’s “Oblique Strategies” or Carse’s “Finite and Infinite Games,” it was full of valuable insights into any & every other human endeavor. Especially the challenging and creative ones. (All three are works I often still think back to here at the dawn of 2025.)

Over this past winter, for reasons I cannot account, I was again obsessed. It is mostly through the piano that I have been exploring jazz this time around. To say I am a poor player would imply I could play at all; I am a primate poking at keys, still speaking the names of notes out loud to navigate. It’s enough.

I have also, naturally, been working on another pretentious little beat tape. A man of many interests, surely, but I am not interested in switching careers. All of this learning is in service to my sideline gig of making dope beats for great rappers. This latest joint is indebted to Shades of Blue: Madlib Invades Blue Note and August Fanon’s 2019 tape Sounding Like Yourself. Rather than covering the same ground, I opted to chop, compose and counterfeit my own jazz breaks & samples. It was exhausting and educational.

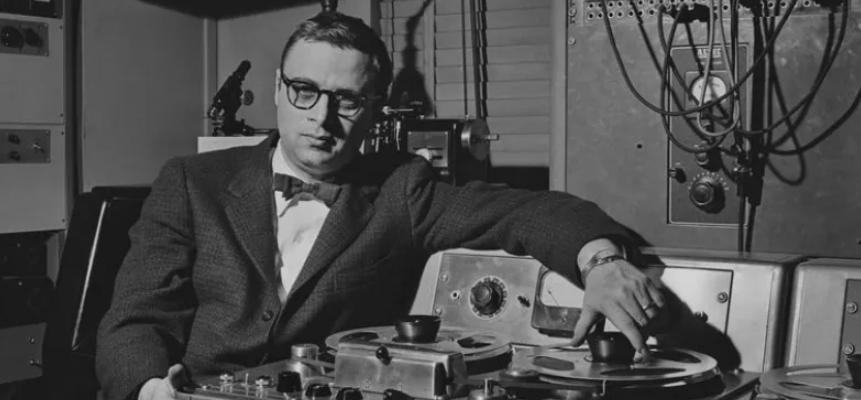

All of our catalogs exist downstream of choices we’ve made, few of them deliberate or even conscious. In terms of the YETI MANE operation, though, I’ve had the luxury of years to plan. I love the overdriven sonics of producers like Apollo Brown or Messiah Muzik, especially when it gets pushed to extremes, like BLOODBLIXING’s entire lunatic catalog. Me, though? I’m a shit-stupid postmodern consumer who grew up on Ninja Tune acid jazz, and I want my product Rudy Van Gelder type smooth.

Rudy was a masterful & meticulous recording engineer whose reign shaped the hi-fi home stereo revolution. He operated out of his home in New Jersey, he was responsible for thousands of classic albums, and he was so paranoid about his secret sauce that he would move his microphones & hide his gear before he allowed any photography in the studio. Obviously, I’m a fan.

Rudy was also controversial, kindling decades-long arguments among the faithful about the nature of recording and fidelity. How real is too raw? How clean is too fake? Rudy was unafraid to wield reverb and compression to enhance the mix, and there’s a straight line from his sweet, saturated tape machines to the RZA cranking his drums through a rackmount SansAmp with the MTV Cribs cameras rolling, the same lineage that connects Ahmad Jamal and Pete Rock. This is the good shit.

“I’m an engineer, not a producer,” Van Gelder insisted to a stringer from the New York Times back in ’05. It wasn’t modesty. He went on to explain: “Someone wanted to put a man on the moon, but it was an engineer who got him there.” Ever after all his decades of accomplishments, he politely refused to discuss details about his equipment or his process. A man must have a code.

I am not nearly so smart: I make beats on computers. Just like in 2005, these days I finish everything in Acid, an ancient DAW which has always made sense to me as an environment for editing and arrangement. To fill in gaps & fuse samples together, I have a dope, dumb and extremely 80s DX7 app called “King of FM” on an iPad, where I also use Koala as a late night sandbox for sequencing ideas and flipping chops. It’s just quicker to perform music than to program it, and besides: “that feel” is mostly the imperfections of human touch.

Since I started doing production work again in ’23, I tend to break everything I sample down to individual notes and create fresh pockets from the ground up. This process mostly involves failing, and I only succeed because I consider all this to be fun. Books can be written about techniques and technologies, sure, but there’s not a lot to this beat life past simply loving the work & loving the culture. Without that, you’re fucked.

Dodecaphonic music is a system that offers over three hundred million possible chord permutations. Most of them sound terrible. The horizon is almost infinite, yet the majority of the choices you can make are still wrong. This understanding extends to all things, especially “flipping samples.” Finding what works for you is a matter of convenience, a dead end loop that will only yield you crutches, roadblocks, bad habits. You have to find what speaks to your soul, what sounds so right it re-aligns your very cells. Biologists call this “frission,” and that aesthetic chill is the only guide that matters out here.

There’s no final answer in these creative arts, but different is always a reliable oblique strategy. I recently realized I start from drums and percussion before I add any instrumentation, and deliberately reversing that has been a goldmine over the course of this project. This also forced me to listen much more carefully to my melodies, ambiance and high end ornamentation. Mashing the right keys ain’t nearly enough, and trying to convey the full feel of some spooky shell chord voicings brought me to the deep lore: old AKAI and SonicFoundry CD-ROM collections of grand piano samples. Building up chords note by note may sound insane but the results are yak butter. The secret sauce is pathological obsession.

I took the same approach on the low end, rolling off the attack and cranking up the sustain for a smoother foundation, a warm embrace. This is not a contrast but a continuation. In 2017, Ryuchi Sakamoto was musing about why he kept playing his signature compositions at ever-slower tempos live. His reasoning: “I wanted to hear the resonance. I want to have less notes and more spaces. Spaces, not silence. Space is resonant, is still ringing.” Even on the uptempo numbers here, I’ve aimed to keep that audible superspectrum humming with life and the echoes of movement in space.

All that said, of course: that shit has to bang or none of this would matter. American Classical Studies is either an unbroken spell or I have failed altogether. My style is downstream of a couple hundred other, better producers, local and global, famous and obscure. Fads will come and go a dozen times every century. I aim to impress my peers & idols.

For those few of you still reading: you’re going to make it. Even if it takes you 20 years, like me. This is an innate & occult artform, and for all our many influences, it’s a solo journey in practice. It’s important to struggle with this shit. Frustration is a reliable indicator of growth. The catastrophic loss of work due to power surges, equipment failures & natural disasters is a traditional rite of passage. Sampling is an artform, and artforms are complex, demanding & time-intensive. Even outlier freaks who make this look easy had to devote years before they could floss like that.

“You can play a shoestring if you’re sincere.” The catch is that we very seldom are.